The Jews of Ukraine: Yesterday and today

There is an anonymous saying shared by the global "tramping" community: "Go far, stay long, see deep." Having spent three months during the summer of 2016 tramping from one continent to the next, I can certainly empathize. It began in Siberia, visiting the family of my Russian-born wife, and continued from Spain to Turkey, and places in between, culminating with several weeks spent in Ukraine. Specifically, I was asked to serve as a visiting lecturer in the International Summer School of Semitic Philology, at the National University of Ostroh Academy (well west of Kiev).

My lectures involved the application of historical and critical methods to the study of my area of specialty-the Dead Sea Scrolls. The program is in its infancy, but the students (non-Jewish by-and-large) are of the highest caliber. Moreover, there was a great deal of satisfaction among both participants and faculty, which included visiting Israeli professors as well.

My time in both Ostroh and the nation's capital, Kiev, provided an excellent opportunity to examine first-hand the overall state, indeed the "prognosis" of the Jewish community of Ukraine. As a starting point, I hired a personal guide and took a detailed tour of "Jewish Kiev," to get a physical sense of the community that was, and that which remains. At the very heart of modern Kiev is Poshtova Square, where celebrations are held and national events commemorated. An imposing equestrian statue adorns the center of this central meeting place. The man on horseback is Bogdan Chmielnicki, considered a George Washington-style national liberator of Ukraine, from foreign domination by the Poles in the 17th century. What is not generally known is that in the year 1647 this ferocious equestrian Cossack instigated a peasant revolt, destroying Jewish communities east of the Dnieper River. As the refugees fled across the river to the west, a massacre ensued at Nemirov, along with many other atrocities. Most of the Jews of Kiev were also murdered during the ensuing wave of bloodshed, which took some 100,000 Jewish lives.

Anti-Semitic incitement erupted afresh in 1881, and again in 1905, when a series of pogroms spread across Ukraine and southern Russia. This was particularly relevant to my walking tour of the city, as I passed a statue of the illustrious literary giant, Sholem Aleichem. Having become a successful writer, especially known for his stories of Tevye the Dairyman (later adapted into the Broadway musical "Fiddler on the Roof"), he took up residence in Kiev. It was the pogroms that convinced him to leave Ukraine, just as the fictional Tevye the Dairyman did, making his way to New York and subsequently Geneva, Switzerland.

In the early 20th century ominous currents in the general culture persisted. The infamous Beilis trial of 1913 involved a Jewish brick factory superintendent in Kiev, who was accused of the ritual murder of a child. The Jewish community responded, organizing proto-Zionist movements such as Hibbat Zion and Bilu. The evidence of these movements was also well documented in my walking tour, as I passed a wall plaque in honor of the woman born in this city, who became an ardent Zionist and who later became Israel's fourth prime minister, Golda Meir.

I was of course obliged to visit Babi Yar, where, on Sept. 29 - 30, 1941 the notorious Einsatzagruppen, the mobile "killing squads" of the SS, rounded up 33,771 Jews and slaughtered them. I also witnessed physical artifacts dating from the Nazi occupation at the Museum of the History of Ukraine in World War II, situated on an imposing hill overlooking the Dnieper River. Included within a single darkened hall were actual uniforms worm by inmates from the concentration/death camps, and an intact guillotine, used by the Nazis to eliminate "undesirables." Indeed, if one looks carefully, there are telltale signs all over the city, not only of Jewish presence over the centuries, but of what they have suffered, during what has been called "the longest hatred."

Nevertheless, the institute in Ostroh is one of many positive signs in today's Ukraine, shaken as it is in the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Crimea. Notwithstanding the troublesome presence of ultra right wing elements such as the "Svoboda" party, with its open Nazi sympathies, anti-Semitism and anti-Jewish incidents are lower in today's Ukraine than in the past, and lower than in many European nations. In the most recent elections, Svoboda was unable to garner even the 5 percent vote required for a seat in the parliament. The fact remains, however, that lessened persecution and greater tolerance does not necessarily translate to a greater sense of Jewish identity. In fact the reverse may be true, as the desire for socio-economic betterment takes the place of Jewish solidarity in the face of anti-Semitic agitation.

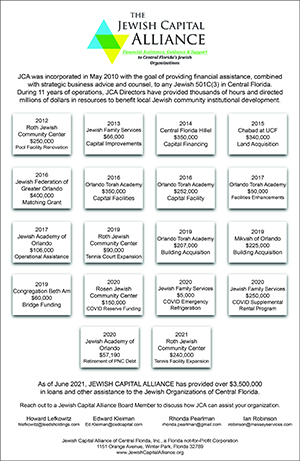

What is the overall picture painted from several weeks' residence in this country? Certainly, there are many positive impressions to be gained from the growth of new Jewish community centers and Hebrew day schools, but it must also be recognized, that while comprising a solid physical infrastructure for the community, these alone are unlikely to rejuvenate a community that is increasingly capable of migrating to proverbially "greener pastures." A Jewish population that used to number in the hundreds of thousands has today shrunk to just over 70,000.

Given these sobering statistics, some may ask whether the Ukrainian Jewish community has a future at all. I was almost prepared to admit it may not-until I encountered the remarkable summer institute in Ostroh. Witnessing the intense level of interest among these young university students made such an impression on me that I must now conclude otherwise. Indeed, if the vision it represents-establishing a Hebrew Studies program in a location where centuries of Jewish civilization and culture have been nearly annihilated-can come to fruition, then one more step may also be taken toward ensuring that Ukraine is again a land that significant numbers of Jews may want to call their home.

Jewish texts needed for The Ostroh Academy

Dr. Kenneth Hanson is reaching out to form a fledgling partnership between the UCF Judaic Studies Program and the Ostroh Academy.

“When I asked the Ukrainian program director what we can do to help, his reply was simple enough: ‘Send books!’” Hanson stated.

Since his return to Florida he has already begun a modest Jewish book drive, focusing on classic Jewish texts (Mishnah, Talmud, etc.) and scholarly works of any kind pertaining to Judaism and the Hebrew language.

“We very much welcome anyone who has such materials to donate,” said Hanson. “Let’s extend a hand to our academic partners in a land where Jewish culture is struggling to be reborn. Let’s make a difference!”

Ken Hanson

An inmate's uniform hanging on barbed wire displayed in an exhibit at the Museum of the History of Ukraine in World War II.

Donated materials may be sent to the Judaic Studies Program, University of Central Florida, Attn: Dr. Kenneth Hanson, PO Box 161992, Orlando, FL 32816-1992

Reader Comments(0)