Viewpoint: Accommodating Jewish students on a large university campus

January 31, 2020

By Terri Susan Fine, Ph.D. and Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz, B.A.

One core value promoted at the University of Central Florida is the emphasis on the individual within a very large institution. UCF aims to be both enlightened and diverse. Students of all religions are welcome at UCF, and like any public university, UCF has established policies supporting religious observance. We believe, as well, that people of any culture and religion should not feel marginalized from the university community because of who they are.

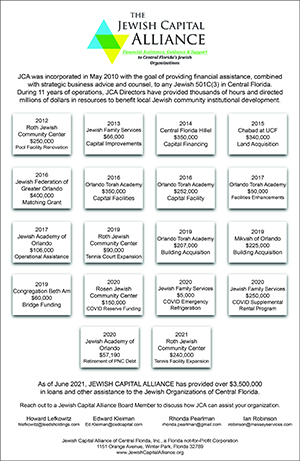

There are so many wonderful opportunities for Jewish students to celebrate their Judaism at UCF that include celebrating holidays, socializing, supporting social justice, observing Shabbat, learning about Judaism and otherwise working together as members of student organizations. Jews are well supported as UCF provides financial support to registered Jewish student organizations through its student activity fees, which also support other student organizations and activities. The university catalog provides religious accommodations for students of all faiths while federal and state civil rights laws protect students from religious discrimination.

Still, a focus on students balancing their Jewish practice with their school obligations is worth our attention.

This article, co-authored by a UCF professor and faculty adviser to three UCF Jewish student organizations, and a recent UCF graduate, describe, in part, Jewish students’ experiences on campus while we explore what UCF policies say about religious accommodation. We begin with five case studies, each of which happened as described although a few details have been changed to protect student privacy.

Case 1: A student is enrolled in a large, 300-student, general-education class taking place in the fall. The professor does not take attendance. There is a warning on the course syllabus that the professor may administer a pop (unscheduled) quiz at any time. Early in the semester the student misses a class to observe Rosh Hashanah. The professor gives a pop quiz on Rosh Hashanah and the student asks the professor to retake the quiz.

Case 2: A student from South Florida is enrolled in an upper division spring course. During spring break the student’s parents ask the student to join them for the first Passover seder. Upon returning to school after spring break the student reviews the course schedule and sees that the final exam takes place the same evening as the first seder. At the next class meeting the student asks the professor to take the final exam early in order to make the trip to South Florida in time for the first seder.

Case 3: Members of UCF Chabad are going to Pegisha, an annual Shabbaton in Crown Heights, in early November. The UCF Student Government Association has allocated monies from student activity fees to offset some of the associated costs such as airfare. A few of the students attending Pegisha have class on Fridays. Before departing for New York City late Thursday, students e-mail their instructors about their attendance at Pegisha; the e-mail includes a co-curricular activity approval form signed by their faculty adviser. After returning to school, the students ask their instructor about making up missed work.

Case 4: A student is taking a class that meets on Tuesday and Thursday. There is a homework assignment due on Tuesday, the second day of Sukkot, and the student notifies the professor during the first week of class that she will be missing class on that day. In addition to the homework, small graded projects are completed in class. The professor tells the student that she may submit the homework late but cannot make up the graded class work given the day that she will miss for Sukkot.

Case 5: Two weeks into the fall semester a student notifies his professor that he will be missing class, a small graduate seminar, on erev Yom Kippur. The class meets one evening per week and attendance is required. The professor agrees to allow the student to miss class provided that his rabbi writes a letter to the professor confirming that the student is Jewish and will be spending Yom Kippur at the rabbi’s synagogue.

In how many of these case studies was the student eligible for religious accommodation? If less than five, which of these five were extended accommodation, and why? To be fair, this is a bit of a trick question as each of the case studies is a bit incomplete.

Do you have your answers? If so, let’s continue.

The next section focuses on UCF policies, part or all of which are common to many universities. Our intent here is not to criticize any institution. Rather, it is to show how seemingly neutral policies may achieve a disparate impact on religious minorities, including Jewish students.

UCF has undergone three religious accommodation rules changes over the last few years. For many years (decades, actually), students were required to notify their instructors in advance if they were seeking religious accommodation. Then, a few years back, the rules changed. To be accommodated, students were now required to notify their instructors during the first week of class if they would require religious accommodation at any point during the semester. It did not matter if Passover took place during finals week; students had five days from the start of class to notify their professors if they wanted to be excused for one or more classes, assignments or exams during Passover. More recently, UCF has extended the notification window by three days, to accommodate students who add courses during the add/drop period, which ends the last day of the first week of classes. By contrast, co-curricular activities that are authorized by an approved university representative are entitled to accommodation so long as the notification is provided in advance of the missed class.

Let’s return to the case studies.

Case 1: Was accommodation required? NO: The student did not request accommodation during the first week of class and was likely confused because there was no scheduled exam that day and class attendance was not required.

Case 2: Was accommodation required? NO: The student’s request was made after the required time frame had expired, during the first few days of class.

Case 3: Was accommodation required? YES: The students attending Pegisha had submitted the required paperwork to their professors in advance of the event.

Case 4: Was accommodation required? YES: The student made the accommodation request during the first week of class. The professor was wrong to deny the student the opportunity to make up the graded in-class work.

Case 5: Was accommodation required? YES. Did the accommodation cohere to university policy? NO. Professors may provide accommodations that are more flexible than those outlined in the university catalog. However, the professor was wrong to require a letter confirming that the student was Jewish and attending synagogue. UCF does not require any student to provide external validation of their religion or religious practice, such as attending synagogue.

College students face many academic barriers. There is pressure to start the semester off right—reviewing the course syllabus, schedule and policies, buying the required textbooks, finding the correct classroom and academic building, finding parking or confirming bus schedules if one is commuting, and other requirements such as navigating a required web-based course platform. Less experienced students may be unaware of their rights or responsibilities when it comes to religious accommodation. Jewish students must begin the semester by checking the Jewish calendar, the secular calendar and their course calendar, to see if, and when, they require religious accommodation several days, weeks or months later.

From our perspective the two approaches (approved co-curricular activities requested in advance while approved religious activities requested during the first 10 days of the semester) might be better aligned. After all, students attending conferences serving Jewish (or mostly Jewish) audiences such as Pegisha, AIPAC, ZOA, JNF, and others, are also likely attending Jewish religious services on holidays that occur on class or final exam days, yet these same students must follow two sets of rules to be accommodated. As well, no student is required to be affiliated with campus Jewish organizations, which adds to their struggle if they are unaware of faculty advocates on campus.

We support that co-curricular activities be the same as those for religious accommodations—notification in advance and not just during the first 10 days of class. This approach will reduce bureaucratic burdens faced by Jewish students on campus.

Terri Susan Fine, Ph.D. is professor of Political Science and faculty adviser for three UCF Jewish student organizations. Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz recently completed his B.A. in film at UCF. During his time at UCF he represented the Nicholson School of Communication and Media on the UCF Student Government, served as vice-president of UCF Chabad, social media manager at Knights for Israel, and in other volunteer roles. The authors may be reached at terri.fine@ucf.edu and jslomowitz1@gmail.com.

Reader Comments(0)